Part 2: Exploring carbon intensity and renewable energy matching

This post describes an approach we have been exploring that uses the MyEnergy emoncms app and work on virtual smart grids with Dominic McCann from Carbon Coop. There’s a good blog and video on what we’ve been working on over on the Carbon Coop blog.

The last post described two approaches to grid carbon intensity that consider the UK grid as a whole. This approach explores what the overall household carbon intensity might be when on-site renewable energy is considered such as home solar but also when renewable energy is bought over the grid, this could be from a green electricity tariff.

If imported electricity is supplied from a 100% renewable energy supplier in the UK: a large portion of the supply will likely be wind energy (54% of good energy’s ‘fuel’ mix comes from wind) and the UK has the best wind resource in Europe. Incorporating grid wind data and exploring matching with wind and solar, means we can really start to test scenarios such as ZeroCarbonBritain in the present.

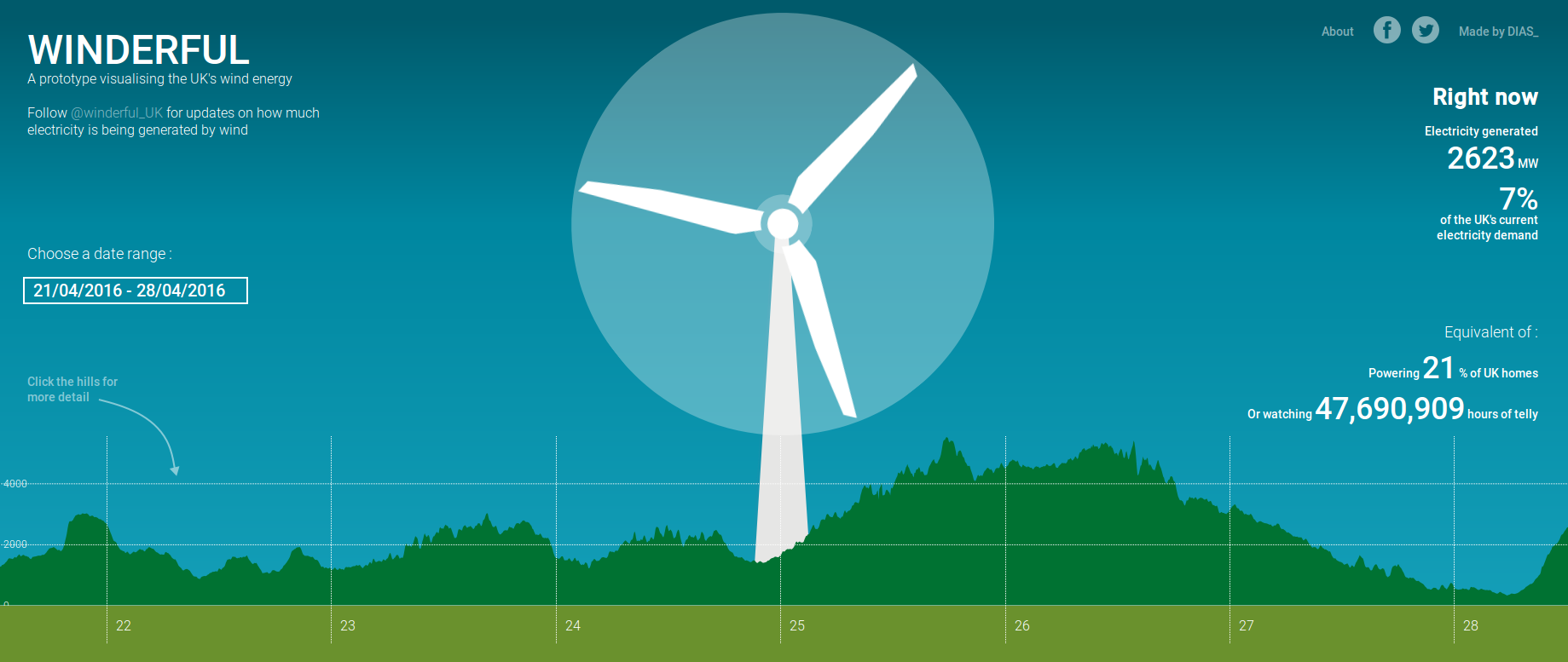

There is real-time data available on UK wind supply and its possible to scale the total UK wind output in order to estimate a household ‘share of UK wind’ in real-time.

Calculating a households share of real-time wind output

Between March 2015 and March 2016 the output of UK wind power was on average 2630MW.

If a household buys 54% of 3300 kWh (typical annual household electricity consumption) or about 1800 kWh this converts to an average power of 205 Watts.

The scaling factor to convert total wind power output in MW to a household share is therefore:

scaling factor = 205 W / 2630 MW

The wind power available at any given moment would then be

wind power available = ( 205W / 2630MW ) x uk wind power output (MW)

If total UK wind power is 4000MW the estimated amount available in this example for the household is = (205W/2630MW) x 4000MW = 312 Watts.

Over the year the average available wind power for the household will work out to being 205W but for any given moment it could be more or less than this depending on how much power is being generated at that moment.

With data on household demand, onsite solar and a share of UK wind, we then work out how much backup supply is needed and from this an estimate of household CO2 intensity.

The backup CO2 intensity could be a single source such as CCGT gas power or a grid CO2 intensity with the wind power component removed in order to avoid double counting. Using an intensity based on grid: coal, gas, nuclear and interconnectors with the wind component removed may help incentivise use outside of peak periods but as discussed in the last post an extended analysis would be needed to establish what’s best from a carbon perspective.

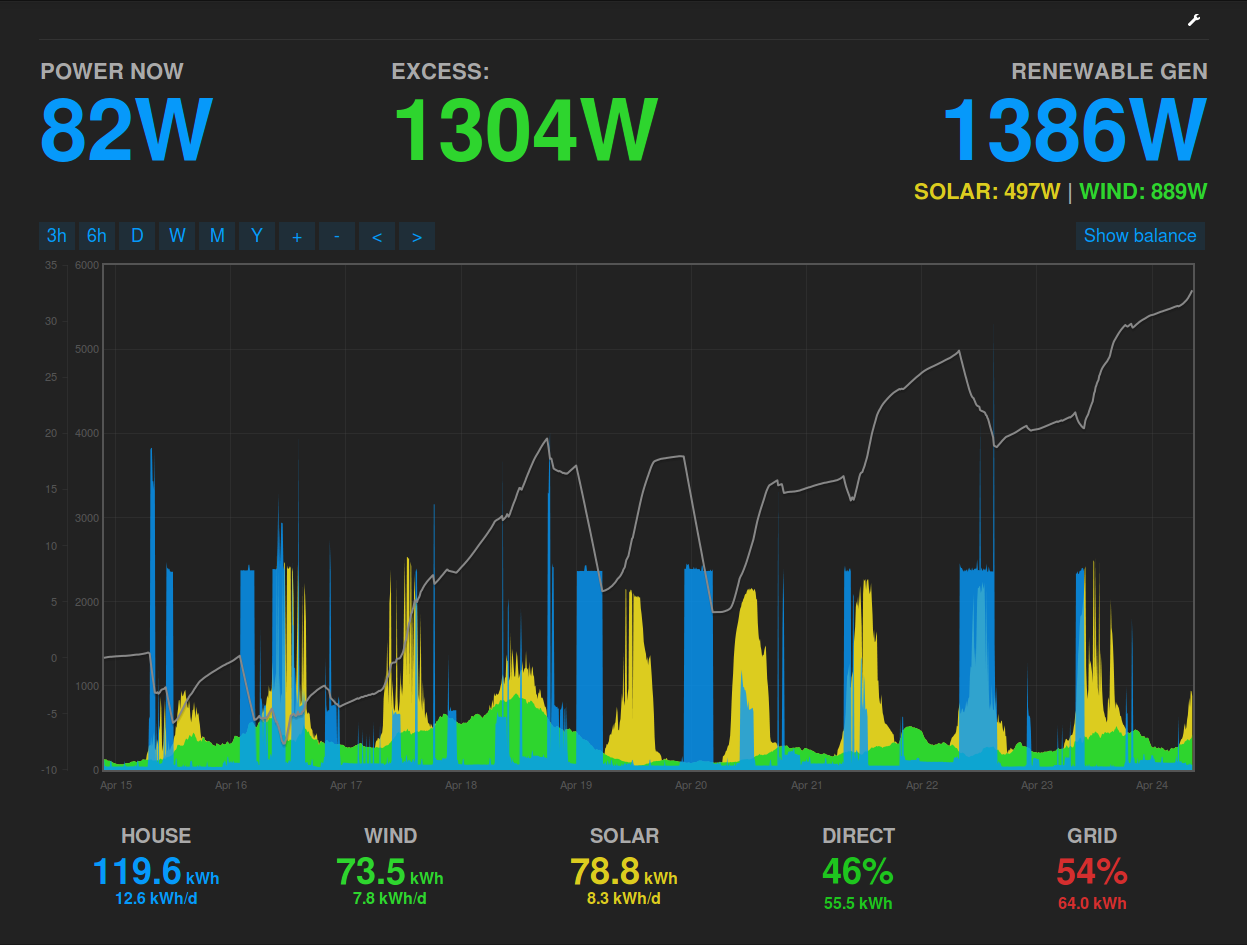

Above: Emoncms MyEnergy App showing onsite solar (yellow), share of uk wind estimate (green) and household demand (blue). Available on emoncms.org or self-hosted installations.

The average CO2 intensities that result from this approach depend on the degree of matching between household demand and the renewable supply. From our experience so far matching can be anywhere between 40% and 70% depending on the nature of the household demand and how much demand shifting effort is undertaken. The resulting average carbon intensity is directly proportional to the level of matching: 40% matching means we need backup supply to cover 60% of the demand reducing the carbon intensity by 40% compared to grid average or perhaps CCGT gas CO2 intensity.

While far from perfect as no account is taken of what is actually happening on the local network, this approach could be seen as a good middle ground between on the one hand saying that all grid electricity has to be counted at grid average carbon intensity and on the other that all electricity from a green tariff is zero carbon at all times. It provides an incentive for demand shifting to times of high renewable output, while reflecting a substantial carbon reduction benefit that should be available from buying renewable energy across the grid.

Excess/exported renewable energy

There is an interesting question as to what happens to excess renewable energy not used by the household in this approach. If the energy is exported to the grid and used by others effectively displacing otherwise needed fossil fuel generation then this carbon saving could offset the carbon emissions emitted by the household when backup electricity was used. The result could mean that regardless of the degree of matching achieved between renewable supply and demand, whether on-site solar or wider grid renewable, the household could achieve net zero carbon by generating and equal amount of renewable supply as demand over a longer time period such as a year. This is a commonly used argument for net zero buildings. On the one hand it makes sense but on the other it relies on there being a wider fossil fuel powered grid in order to displace the fossil fuel generation and it substantially removes the incentive for renewable supply/demand matching.

Displaced carbon

Perhaps a better way to look at the displaced carbon issue is who is it that actually gets to claim the zero carbon benefit of that electricity. It would make sense that exported electricity is sold and then bought by the other party, once you’re buying renewable energy you would expect to be able to claim the zero carbon benefit of that energy as the user. Counting the exported electricity if bought by another user as displaced carbon would result in double counting in this case.

This is somewhat complicated by fact that exported solar pv electricity is not metered for small domestic installations in the UK. Instead the amount exported is assumed to be 50% of total generation. The exported electricity is paid for at around 4.91p/kWh but not measured. It’s not clear who gets to claim the carbon saved.

Next: Aggregation

The degree of matching can be increased by aggregating supply and demand across several households. Not everyone boils a kettle at the same time or a cloud passing over one households solar pv system may not be passing over another’s. We have been testing with a limited number of households so far, the effect of aggregation on the degree of supply/demand matching which I will come on to in the next post.

To engage in discussion regarding this post, please post on our Community Forum.